I wanted to be the Devil myself

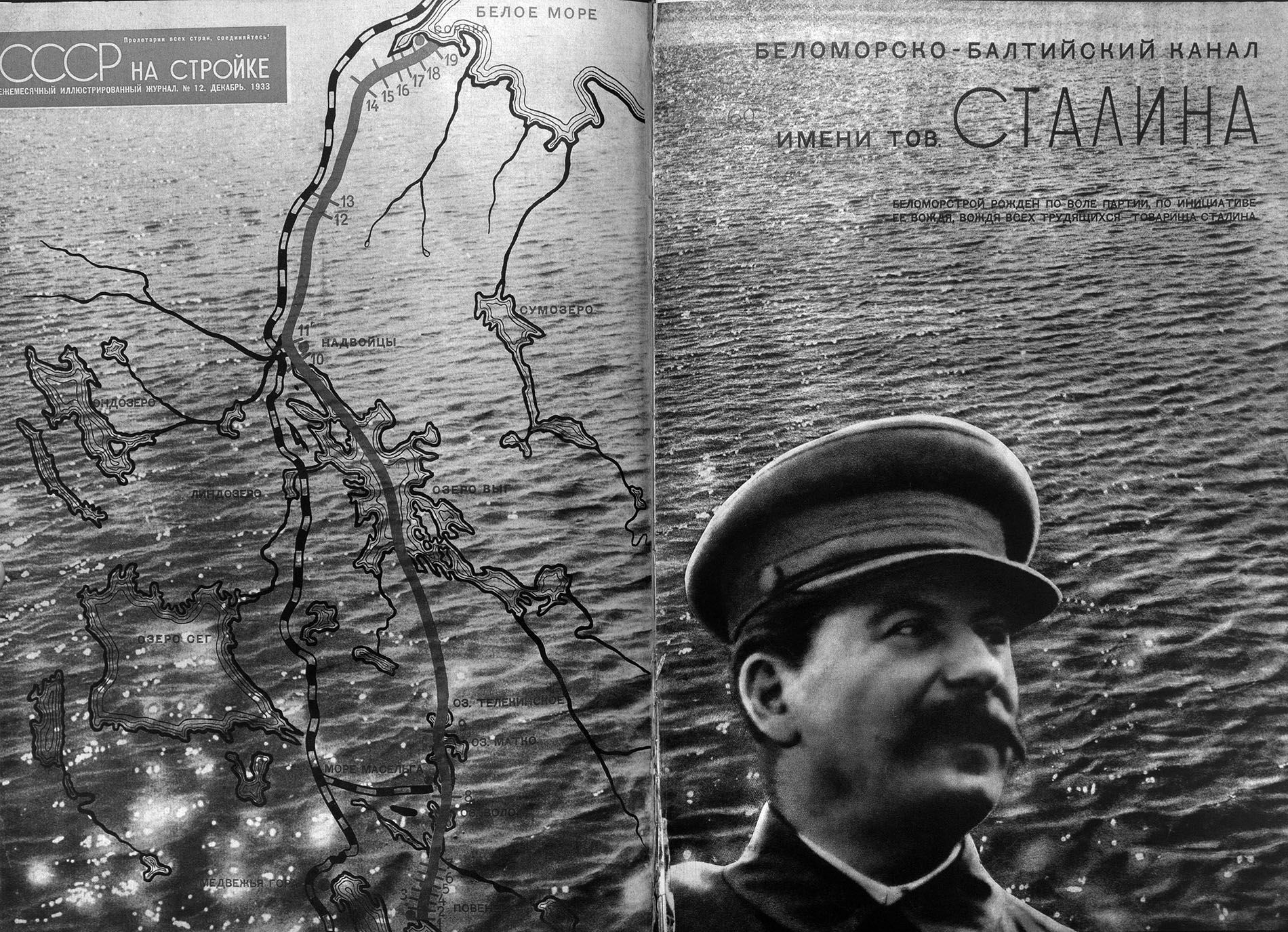

The forgotten history of how a Soviet photographer glorified the Gulag's White Sea Canal.

During my last two trips, I worked in the local archives, searching for traces of work by the Soviet photographer Alexander Rodchenko, who—secretly working for the Soviet authorities in 1933—photographed the USSR’s first major construction project to use Gulag prison labor. In a special report, I writes about my trip and research, and how memories of the people who built the White Sea Canal have faded from Russia.

The White Sea Canal. Karelia. 2009

Yury Dmitriev, a 53-year-old man [in 2022 he is in the prison], is dressed in military camouflage, with a German shepherd next to him. In his chest pocket, a bulge in the shape of a gun is visible. "Why do you need a gun?” I asked. "This gun?” He took it from his pocket and showed it to me in the palm of his hand. “Because the civil war is not over.” I looked at the gun and asked awkwardly, "Why did you arrange to meet me at the cemetery?" The historian smiled and said: “So that you’d be scared. Ashamed and scared.”

The historian Yury Dmitriev—from the Karelian Commission on the rehabilitation of former political prisoners under Stalinism—has arranged to me to meet in the forest, near the canal, near the unknown burial grounds of the 1930s. Along the canal there are scores of them, many of which have not yet been identified. “It's the purpose of my life as a person and as a historian to look for the tortured and executed, but a whole lifetime still isn’t enough. Now, from archival documents I can confirm and point out the pits and ditches where Chekists buried around 86,000 people.”