Republic of the incurables

Indeed, Karabakh is unlucky. A small mountain republic that somehow believed in the immutability of global democracy

You know, there are many places around my home where I fought, but I don’t feel like I ever left the war—or that it ever ended. For a while, I’ve had no rifle, no grenades, no mortar. I have no weapons, but I also have no sense that the war is over. It continues. Not only inside me—no. Around me. Here is the proof: trenches, shell casings—they haven’t disappeared with time, they haven’t disappeared from this land. They’re waiting for someone to come back to them. If not me, then my son. Or my grandson. I don’t know if you understand.

I read about you on the internet—you came to the war, and then you left. Always. But I didn’t come to the war. The war came to me. That’s the difference between us—not that you were taking pictures and I was killing [...]

Formally, "healing through democracy" never happened. More than twenty years after the Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh declared itself, no state in the world has recognized the right of the Armenian population in the NKR to self-determination. But first came war, and tens of thousands of human lives were lost.

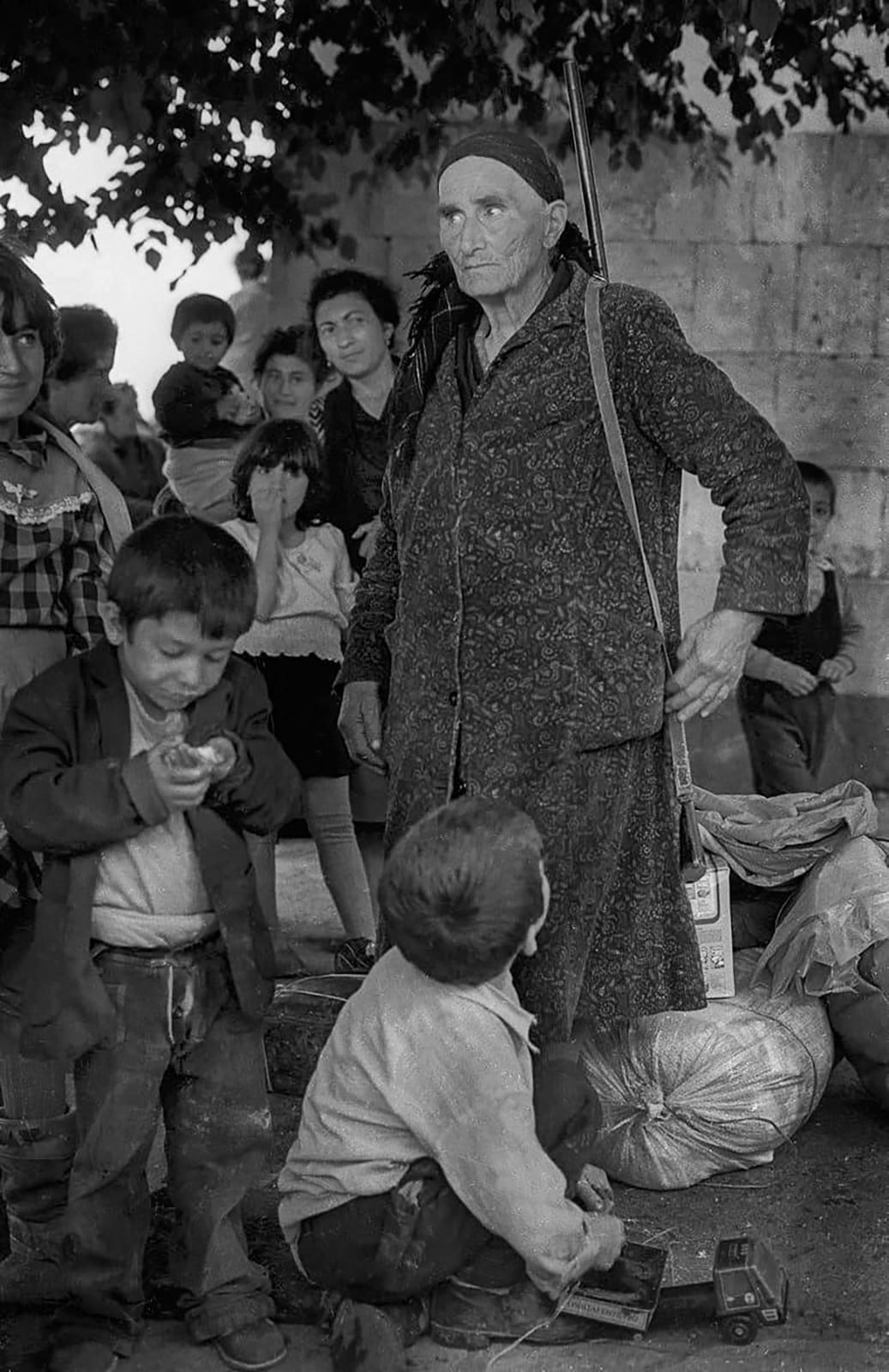

In the late '80s and early '90s, I visited Karabakh often. There was war—a war unknown to the world, but no less bloody. The Soviet Union’s agony and collapse left Moscow unable to properly address the Karabakh issue, except to send in federal troops—soldiers untrained in localized warfare and interethnic conflict. Censorship meant the conflict was rarely covered in central media. During the 1991 coup in Moscow, the war in Karabakh seemed to lack even minimal news value. After the USSR’s fall, Russia considered the conflict a private matter between Armenia and Azerbaijan. And so, one of the bloodiest wars on Soviet soil became—and remains—a war unknown.

In those days, I traveled to Karabakh through Agdam—its "gateway"—a city then populated entirely by Azerbaijanis. From there, with Soviet Army help, I reached Stepanakert, the Armenian capital of Karabakh. Agdam no longer exists on Armenia’s maps. Nor in reality. Only ruins remain. Walking through them evokes unease, then dread. Empty houses, shattered streets, grass growing everywhere. Even birds don’t sing here. Only silent flocks of sheep and cattle roam from house to house, street to street. No people, just domestic animals. Perhaps because they trust humans—and don’t know that humans laid mines here. Even now, livestock and children die from mines. Because they don’t know fear.

Sometimes a car passes along the broken road, and the driver eyes me—a man wandering with the animals—as if to ask: who are you? An Azerbaijani returning home? A spy? No one else walks here. It’s too frightening.

Once, on Agdam’s outskirts, I entered a teahouse and met journalists from France, Germany, Russia—freelancers and stringers who came here on their own, without permission, defying censorship to tell the story. That teahouse is gone, as are some of the journalists I met. One died in a shell blast, two others of alcoholism. That’s what I remember, twenty years on.

"Where they sell watermelons—that’s where Agdam was," one passerby told me. "At least they’re not selling grenades," I joked. But along the road near the ruins, watermelons are indeed for sale. Were the city’s ruins worth a melon field? For some, this became a rhetorical question only decades later.

Agdam to Askeran is just a short ride. On a Soviet APC it took fifteen minutes. In a car—less. Today Askeran is the "opposition capital," and Karabakh is holding elections for its third president—unrecognized by the world, yet real to its people. And what I saw in Askeran felt ancient—like a scene from Rome or Greece in democracy’s early days.

Peasants, farmers, the rich and the poor, citizens and politicians—all gathered in a schoolyard under the open sky, the mountains of Karabakh forming its amphitheater. Everyone wore their best clothes. They had come to hear and discuss the presidential candidates. Hundreds sat with red roses, on benches, on grass, under cypress trees. When the candidate arrived—on time—they rose in silence. I didn’t understand a word of Armenian, but I understood something essential to democracy: respect and trust.

Being too Russian in my ways, I asked outright: “Who will you vote for?” Violating the sacred rule of secret ballot. But Karabakh’s citizens politely deflected. No one told me. At first I thought they were afraid to speak honestly. But that day in Askeran, I understood: they weren’t afraid. They simply respected the process.

That realization hit me hard. Maybe because I still feel ashamed about what passes for elections in Russia.

“I remember you,” a police major told me. “You came to Askeran at night, from the Turkish side—we arrested you as a spy.” I remember sleeping on a police station bench under shellfire, covered by a soldier’s coat. I didn’t feel arrested. Just dead drunk.

In truth, we came not from the “Turks” (as Armenians call Azerbaijanis), but “from across the river,” as my drunken photographer comrade told the police. A phrase leftover from Soviet-Afghan war slang.

And yes, we’d crossed the river—on foot—during a bombardment. The brandy factory in Askeran was on fire. Armenian soldiers had been washing with the green brandy in lieu of water. We drank it too.

Thinking we had a newsworthy story, we ran into an Armenian patrol instead—and landed in jail.

I told the major all this, twenty years later. He laughed, then turned serious. Still, he didn’t let me into the police station again: “Once is enough,” he said. So I headed back toward the old Askeran front line.

Driving a rented Niva, I found the hills, rivers, trenches I’d once photographed. It all came back. The exact spot from which I’d watched the brandy factory burn. The positions of tanks, mortars. The people. My own state of mind. The place stirred memories.

“I’ll tell you this, Oleg,” said a soldier I’d photographed then, “you’ll never forget this either, even though it wasn’t your war.”

His name was Eduard. He met me on the old front line.

“You arrived,” he said, “when I found a man’s leg near that bush. Just the leg. Maybe the rest had already gone to the hospital—or the grave. I don’t know. We buried the leg over there. Then you showed up. Then we drank that terrible green brandy. I never drank anything like it before or after the war…”

Eduard showed me a folder of papers, clippings. One was a photo I’d taken—right where we stood. “I followed you after the war,” he said.

I felt embarrassed. Couldn’t even remember when that photo had run in Izvestia.

“I didn’t follow you,” I admitted. “I didn’t even follow my own photos. Have you been here since?”

“No. This is my first time.”

“But why? It’s only twenty minutes from your house.”

“You don’t get it, Oleg. I’ve fought in so many places around my house. But I never felt the war had ended. I don’t have a gun now, or grenades. But the war goes on. Not just inside me. Around me. The trenches, the shells—they’re still here. Waiting. For me, or my son. Or grandson. I read about you online. You came and left. But I didn’t go to war. War came to me. That’s our difference—not that you took photos and I killed.”

We stood on a hill near Nakhichevanik. From there we could see Agdam’s ruins, Askeran, even colorful, pre-election Stepanakert.

“So now what?” I asked.

“Now what?” He pointed toward the border. “You hear that? Gunfire. Every day. When I volunteered to fight, my son had just been born. My friends said: don’t go first—you have a son. We’ll go—we don’t. And now? My son has already served two years on the border—where they still shoot every day. No, we’re not leaving. The war must leave us. That’s what now.”

Driving back to Stepanakert, I wondered why these "soldiers of the past" treated me as a comrade, even a brother-in-arms. I’d done nothing good for them—at least I hoped, nothing bad either. I didn’t fight. I refused a gun. Yes, I spent nights in trenches, in mountains. I came and went. They stayed. I asked Eduard why.

“You don’t understand,” he said. “You were like Martians. Journalists were rare. No one invited you. You came on your own. Young, curious. You talked to us. Took pictures. You gave us hope. That we existed. That someone cared. That someone would know before we all died. You can’t imagine how much that meant then—and still does.”

This is memory, I thought, walking through Stepanakert, recognizing familiar places. Human memory needs occasional proof of past reality. A man from the past, like me, becomes living evidence. Bullet holes and shell marks fade into the background after twenty years of half-war, half-peace.

"Who are you looking for?" a beautiful woman asked from her window.

"The remains of war," I joked.

"No need to look," she said. "They’re everywhere. Were you fighting here?"

"No, just photographing."

"Then let me tell you: we still live in war. We’re almost used to it. It lives in our hearts, in our heads. We talk about life, but we think about war. We give birth and think our children may die in war. It wasn’t our fault war came—but once it did, men, women, even children took up arms to drive it away. Now we have no weapons. But the war hasn’t left. It’s always nearby, like a shadow. Every nation has a right to peace. Every one! But the war won’t leave us. That’s unbearable. The pain of the past, and the pain of what’s to come—they’re both here. In the present. Every day. That’s what I wanted to tell you."

As I left, she called out again, handing me a bottle of mulberry vodka through the window.

"Why?" I asked.

"Because you were with us during the war. And because you listened."

At a bar terrace, I watched buses arrive with international observers for Karabakh’s 2012 presidential election. All looked busy and important, with folders and documents, bowing like Japanese samurai.

What were they doing here? An election unrecognized by the world—and yet international observers arrived.

"The government of Karabakh invited us as independent observers," explained Polina from the Czech Republic.

"So are you representing the Czech Republic—or just yourself from the Czech Republic?"

She laughed. "Probably just myself. But I can speak about this election in Parliament. Or write about it. Yes, it’s unofficial—but important for Karabakh. What about you?"

I couldn’t answer right away. Then I said, "I came to the war—with a twenty-year delay. But everyone tells me the war is still going…"

Then we drank. Then drank some more. Observers from Germany and Russia joined us. "These were honest elections," each one insisted.

And I believed them. In a small republic where everyone knows each other, where no one recognizes them, where war and poverty prevail—it would be hard to fake an election.

Everyone here, including the President, probably needs healing. But they don’t get it—not through any known means. They have a Constitution. A flag. A President. Elections. Self-determination for 150,000 people. All the symbols of a state. But no healing. Because there’s no recognition. And without recognition, the war stays.

These were my thoughts—slightly drunk—that I shared with the observers.

"You’re partly right," Polina replied. "They’ve done almost everything to be recognized. But the world has done nothing to recognize them. Recognition only comes through two-sided policy. But the international community is guided by very old democratic principles, which are often just declarations—and by modern political realities. According to the old principles, Karabakh should be recognized. But the modern reality means no one can. There are more and more republics like this. But fewer and fewer solutions. Maybe none at all—unless we change the principles themselves: like ‘the right of nations to self-determination’ or ‘territorial integrity’…

In a way, the world now resembles the old Soviet Union. On paper, everything’s perfect. In practice—it’s a mockery."

Indeed, Karabakh is unlucky. A small mountain republic that somehow believed in the immutability of global democracy. No resources. No industry. Agriculture in decline. A place where people’s souls are haunted by war. And yet—they must individually answer for the failures of international law, for the fiction of democratic principles, for the "political realities" that contradict the reality of democracy. Why?

I’ve traveled a lot—professionally and for pleasure. But I’ve never found a place I wanted to stay.

Except here.

Not twenty years ago. Now.

Not because the brandy factory works again, or because beautiful women still notice me.

But because here, in Karabakh, people still believe in their fate—with a faith I haven’t seen anywhere else in the world.

At least not where I’ve been.

Oleg Klimov, Stepanakert–Moscow, July 2012.

Donate to my work as a freelance photographer.

P.S. The 1994 ceasefire agreement brokered by the OSCE Minsk Group did not change the official status of Nagorno-Karabakh as part of Azerbaijan. While a self-declared republic, the Republic of Artsakh, was established and governed by ethnic Armenians with support from Armenia, the agreement established a line of contact separating Armenian and Azerbaijani forces, essentially maintaining the status quo. However, the 2020 Second Nagorno-Karabakh War and subsequent agreements led to Azerbaijan regaining control of occupied territories surrounding Nagorno-Karabakh and parts of Nagorno-Karabakh itself. By 2023, following a military offensive and ceasefire, Azerbaijan had gained full control of the region, including the areas previously controlled by the Republic of Artsakh.